Van Dusseldorp's Future of Events (Bonus story)

The Big Bamboozle, 100 billion cassettes & live events.

This is a bonus story - let’s call it a pretty random addition to issue no. 10 of Van Dusseldorp's Future of Events. This is a story about how I fell in love with live events, what events mean to all of us, and how we bottle that feeling in a digital age. You can find all previous issues here!

Prelude

This month Philips engineer Lou Ottens died, 94 years old, the inventor of the audio cassette. More than 100 billion cassettes have been sold since its launch in 1963. Twenty years later, the same Ottens and his team developed the CD. Tip of the hat to Lou Ottens!

My First Events

Let me take you back to 1980, the cassette tape era. When I was 15 I joined a local band in Tilburg called the Big Bamboozle, along with around 30 others - art students quite a few of us, but also people from other schools, other backgrounds, a motley crew.

Some with real musical talent and others like me, invited along for good cheer or perhaps just because I owned a Philicorda electronic piano. Another Philips product!

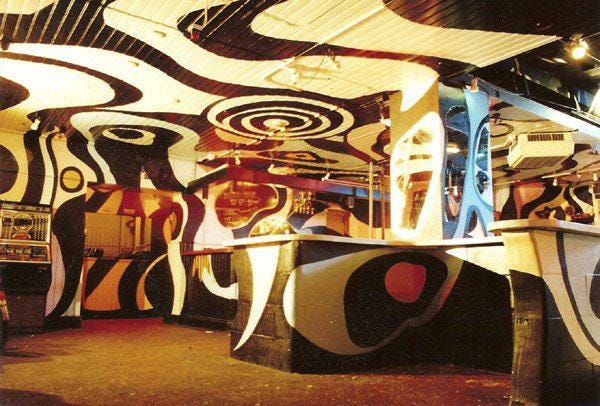

Early eighties youth unemployment brought along a specific DIY/punk culture. We had our rehearsals in a local nightclub called De Spoel and would dance the night away afterward to the latest new wave tunes.

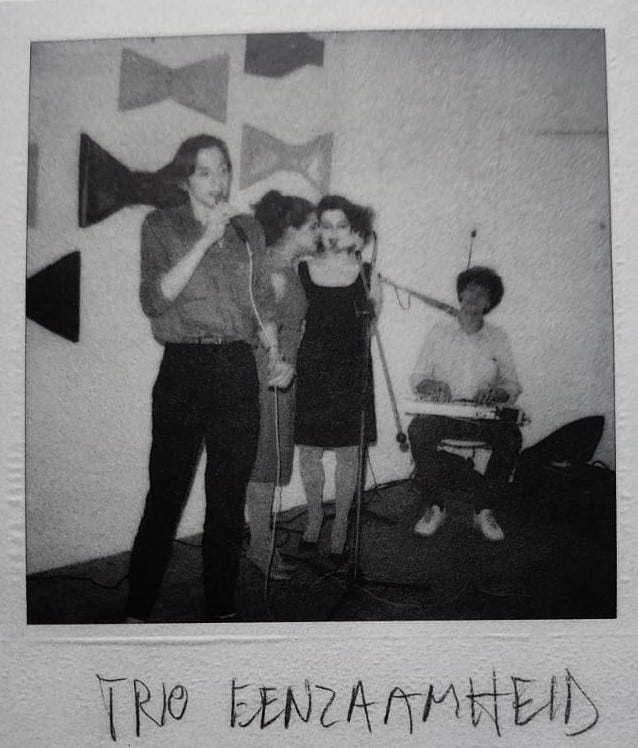

The Big Bamboozle performances were joyous if anything: we had fun on the bus rides, we dressed up to themes, we interacted with the audience if they turned up at all, and special acts included dance, spoken word, and music, and often transformed into new bands.

In 1985 we organized a whole festival. At some point or other I was part of the Big Bamboozle, Trio Eenzaamheid, the Moniek is Bleyband, Titanic Combo, Schopenhauer Smiles, and the Miners of Muzo. All this without having any particular musical talent. It was a splendid time to be.

Interlude

There is an interesting history of Philips and the NatLab and their role in the digital industry. Below you can listen to composers Kid Baltan (Dick Raaijmakers) and Tom Dissevelt explaining how electronic tape music is made.

Baltan is the inverse of NatLab, which is short for Philips Natuurkundig Laboratorium: Philips Physics Laboratory - for a few years a research lab for the brightest minds who could research whatever they wanted.

They hired artists to help develop musical instruments. The Philicorda was one of the resulting products, as were the first synthesizers. Electronic music began in the Netherlands, based on Philips tech.

A famous song with a Philicorda sound? Chris Montez, Let’s Dance, 1966. One of the earliest synthesizer songs is Song of the Second Moon (1957), by Raaijmakers & Dissevelt - a homage to the Sputnik I satellite.

The original purpose of the compact cassette tape was for dictation, not music. Later on a different kind of Philips cassette was also used as the first mass storage device for early personal computers in the 1970s and 1980s. And around the same time, Philips established ASML - now the largest supplier in the world of the machines to make computer chips. One company, one lab.

But let’s go back to neighboring Tilburg and our local scene.

Local & physical & rare

Unaware that we were on the cusp of a digital revolution - we lived pre-digital lives. There is something about that culture I am trying to understand in relation to the world of unlimited connected content that we live in now and the future of events.

I am not sure how exactly we found each other for starters - we all danced at Swinge bij Dinge at one point? Most of us did not have a fixed-line phone but were sharing one with a group of students. I still have boxes full of letters and postcards.

Our musical tastes were quite random - punk, new wave, jazz, soul... A lot of us took our musical cues from Rinus, a guy at the local record shop (Tommy Records). But we mixed up the genres as well.

Siouxsie & the Banshees, The Specials, Julie London, Rip Rig & Panic, Nina Simone, Django Reinhardt, I have the records right here in front of me. There also were these small cultural crazes in our network - not just about music. One year, we shared around a copy of the novel Ferdydurke, a discovery by trumpet player Wim. Hewald and friends put on a rendition of Ubu Roi. Eugene Geene sang a Willi Alberti schlager, standing on the stairs of our art school. Both the books and music of Boris Vian were a big hit for a while (Je bois..). Does Carla Bley know there was a cluster of fans in Tilburg so strong we started a cover band? At one time we were all looking for Chet Baker Sings & Plays, considered an unfindable record.

Eclectic stuff indeed. Just a rare and random selection presented to us from our own in-person super random social network. What we could find was shared locally and subcultures were - even if they were inspired by international waves - super-local cultures. We needed to get together to share anything: ideas, music, jokes, dance moves.

Our performances were hyperlocal as well - the audience had no idea what they were going to hear, we never made a record after all. They just turned up to their local venue, curious for what that evening would bring. We physically passed on objects to each other: books, records, mixtapes.

Digital & ubiquitous

I am not sharing all this to make you dive into this weird culture selection (although it would not hurt you to put on some Chet Baker every once in a while).

Our social objects were rare, hard-to-find cultural objects, that we shared and cherished. Books, records, and the best of all: mixtapes. Your own personalized selection of the world of music pulled together from records & radio recordings - also the best gift ever. (The Guardian published some lovely mixtape stories).

Cue 2021, and with a few taps on our keyboard we can find even all of the above in seconds. My kids - teenagers - have everything that was ever produced on tap - music, movies, series, stories, TV moments, dance moves…which is fantastic. Especially now that local and physical gatherings have been erased from their lives.

However, if everything is available at any time, and anywhere, what is the social object worth? Make digital into physical again by selling merchandise? Just slap on an NFT to create artificial scarcity? (To my delight, Till Grusche's piece about NFT’s this week has a mixtape story as well).

I am not thinking of financial value but value in the sense of important, worthwhile, worthy of our attention. For event organizers, one of the ways to make things ‘‘rare’’ again is to make them ‘‘live’’. And as we are finding out this year, ‘‘live’’ can also be online & live.

It's great that we now live in a world where all content is available anywhere 24/7. All music, but also all talks, all ideas, all conversations, crossing geographical boundaries, time zones, social spheres.

But in that world, events still do something amazing and special: they bring us together in one moment. In a world of 24/7 content, maybe being together like that is even more valuable than it's ever been.

So my take: online events are here to stay as a conduit for being in the moment, a way to create value, giving the gift of the singular experience, something to share.

We just need better ways to be online together.

Better formats, better online presence, other kinds of connections, and actions, interfaces. This newsletter will be watching every step of the way as we try to figure out what being together online can be.

Great examples? Tell me about it!

Normal service will resume soon….

kthxbye!

Monique

About

Van Dusseldorp’s Future of Events is a newsletter by me, Monique van Dusseldorp. I am a freelance curator and moderator of tech and media conferences (more here). I love to hear from you! Mail me or connect with me on LinkedIn and Twitter. And do tell everyone to sign up for my newsletter! :-)

🎵 Postlude

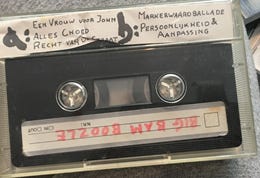

One more thing, the Big Bamboozle! How did the bookers at the clubs find us in this super local physical world? Of course, of course, we sent out demo tapes!

I had forgotten all about this, had it not been for Marco van Dalfsen of Diggin Demos and a rare historical find. From 1980-1985, Amsterdam club Melkweg received almost 1.000 demo tapes, and all of them were registered in the Melkweg Cassetteboek - incl handwritten notes on the music, and whether or not the band was to be booked.

Marco not only published the complete book he also digitized the tapes and put them online. What once was, recorded, to be shared on tape, sent by post, kept for 30 years, now digitized and published and shareable again - 🤟